ARTICLES, I NEED HELP: TEEN SUICIDE PREVENTION

My Father’s Suicide

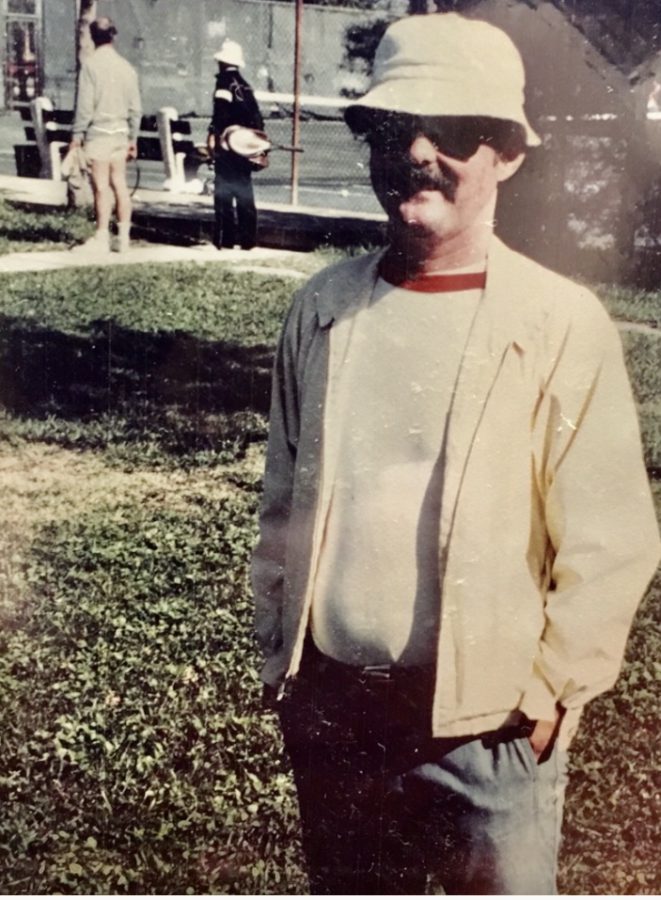

In his early 20s, my father was diagnosed with lupus – a chronic autoimmune disease that occurs when your body’s immune system attacks your tissues and organs.

Several years after his diagnosis, my father married and became a father of two: To both my sister, Lisa, and myself.

Despite chronic fatigue, arthritis, and sensitivity to the sun, my dad was determined to be an active father. His lupus had little effect on our quality family time – we would often go to nice restaurants, movies, malls, and parks. He seemingly would push through his pain so my tight-knit family could make valuable memories together.

After being read his last rites in my senior year in high school, he survived a one-month coma. His love as a father fueled him to live long enough to see us graduate from high school and college, and Lisa to marry and have two daughters.

He and I were even planning to visit Georgia – where Lisa lived – because she was expecting her third child – her first son.

By then, my father had been battling lupus for over 35 years. Symptoms of cancer began to deteriorate him further. I decided to move-in with him for the first time in five years. I wanted to live with him full-time to assist him in his disease, instead of only seeing him on weekends.

During the time I lived with him, I was working a second part-time job at night. I would finish my shift and rush home to check on him in the morning.

One day during my shift, I felt compelled to check on him in the middle of the night. I wanted to know that he was doing alright, even if it meant waking him up.

His room was dark and barely lit from the hallway light, but I could sense serious trouble by his unnatural sleeping position.

I walked into his bedroom and was shocked at what I saw. My father had committed suicide.

My father had been raised with strict beliefs that prohibited suicide. He never threatened it, talked about it, or even left a note explaining why. I was shocked and confused.

I couldn’t process what I had seen on that tragic night. The only comparison I’ve been able to make is both of us being involved in a car crash, and I was the sole survivor.

In the aftermath of my father’s suicide, the traumatic and indelible experience made waves in my life personally, professionally and financially. It was too painful to deal with. For at least ten years, I was searching for ways to cope with the tragic loss of my father.

After years of spirally downwards, I could no longer continue facing his death on my own. I opened up to some of my family members and friends about my pain. I eventually sought the support of a counsellor.

My healing process was prolonged and gradual. Every day was difficult, but I learned how to heal and adapt. With the help of my supports, I began to move forward so I could lead an active, productive and healthy lifestyle again.

I started raising lupus awareness and fundraising on social media; and www.liftingboca.com and www.liftingawareness.com in my father’s memory for the next three years.

It not for the inspiration of Gabrielle Union; and the support of my sister and wife, Cymonie, I would never have been strong enough to write and speak publicly about it, including magazines, social media, and churches.

I even wrote a book, The Light At The Beginning And End Of The Tunnel. Suicide rates are increasing – some are failed attempts and, some, unfortunately, successful.

Confronting the fact that a loved one committed suicide may be a very overwhelming experience, but it is possible to learn how to heal from it.

I learned to no longer have recurring nightmares about the night I discovered that my father committed suicide and my only memories of him are as a loving son, father, and grandfather, which was a major milestone.

It may be a very formidable foe, but less daunting than not dealing with it and living a life of unbearable suffering.

I might have accepted that my father ended his own life, but I refuse to accept that his life – or death – was in vain so I now truly face the enemy head-on by educating and inspiring others.

By Stephen Hinkel